September is the best time to be outside — the sun is still warm, and the bugs have largely disappeared. With the knee-high weeds also dying back in the forest, Beau and I have found ourselves drawn deep into our woods exploring the wilder parts of our land — there’s an entire section which is practically inaccessible, barricaded by fallen trees. We tried to make sense of this mysterious area, tip toeing along the top of the double-wide wall lining this side of the property. The glorious autumn sun shined down through the trees, as we climbed our way above, below, and around the huge branches blocking off parts of our rocky wall trail.

Back in the Spring, some of you will remember our efforts cleaning up our backyard, downing trees to reveal the stone walls built in a wide curve around the property and deep into the woods. My elbows are only just recovering from dragging branches into burn piles for weeks as we cleared the overgrown area.

Once our Spring cleaning was complete summer set in, and we were so occupied tending our veggie garden, that we barely ventured into the forest — increasingly teeming with a sea of waist-high wildflowers, weeds, ferns, and buzzing beneath the trees — and the invasive, thorny Japanese Barberry that we worked so hard to cut down (braving it’s pricklers) which grew back with new vigor, thumbing their noses at our useless efforts! Digging them up from their roots seems an impossible, way too prickly task.

With the current weather luring us to the other side of the stone walls we had worked so hard to reveal this Spring, we headed for one of my favorite parts of the forest: a stretch of double stone wall which was once a farm road. A few trees have grown within this old road, but restoring it seems within reach. When we first arrived there was a tree laying straight across the road — completely blocking it. So the first job Beau tackled when he bought a chainsaw last year was to cut that downed tree out from the farm road. The first time we could actually walk all the way down that double-walled section was so satisfying.

We have been trying to decipher where this road went, thinking we might tease it back out of the landscape, wending its way along a stone ledge overlooking the grove of apple trees, and through the double walls to an opening that crosses the bottom field, leading to the barn.

Slowly we are clearing the branches and fallen trees from the road — and finding it’s tributaries — one arm turns down to the orchard, another wends round to the grand sugar maple and a ledge with a view over the apple trees. Another path heads to the stone arch an artist built for us in a pile of stones built up beneath an apple tree.

The more we walk the old farm road, and drag away the tree trunks that have fallen over it, the more the road is revealed and our mental map of the forest becomes clearer. We pile the branches and tree trunks in a mound, up against the stone ledge below.

I worried at first that we were just pushing one mess of branches into a new mess of branches a few feet further along, but now I look at this structure piled up against the ledge and call it a “habitat” — and imagine a woodland creature burrowing in it. Salamanders. Organic material breaking down into the soil and sequestering carbon. The life in the soil.

Trees, and their forest systems, are truly to be revered. In this light, we have been cautious, and thinking hard about how to best steward, and at the same time enjoy this forest. How much do we clear, to let light in for the apple grove? How much extra light might send the apple tree into shock, doing more harm than good? Serendipitously, this summer brought us into the orbits of three of the most revered tree ecologists in New England, as if called by fortune, to help us find answers to how to tackle this huge task.

The first forest expert, Robert Leverett, was revealed when I had the pleasure of reconnecting with my college piano teacher who was visiting nearby for a week. We hadn’t seen each other in about half a century! She introduced her husband with a sort of reverence, as a celebrity in the tree world. As soon as he smiled and started to speak with his charming southern accent, I began to understand why. He has spent decades deeply involved in the ecology of trees and carbon sequestration, cataloguing all the old growth trees and forests of Massachussetts and more.

Later in the summer, I learned that the amazing apple expert, John Bunker, was giving a talk at the local Island Heritage Trust. Passionate about heirloom trees, and old apple tree genetics, he was interested in visiting some properties in Deer Isle with old apple trees. Having wondered what it would take to rescue our light-starved orchard of apple trees, surrounded by towering pine trees, I volunteered our farm as a possible destination. On the appointed day, 8 cars suddenly descended on our property (we have never seen such traffic come up our rocky drive). I had no idea that this visit would happen in the company of an entire entourage — a journalist, an academic, and at least 3 organizing families from the island — hanging on his every word. “Every apple tree is unique. They have DNA like humans. The different apple varieties you think of are clones, grafted onto these apple trees.” He pointed at the apple trees on our property. They are all “seed apples”. Each one unique.

As we led the group in single file into the thick and buggy mid-summer forest, the entire contingent of apple tree enthusiasts followed us deep into the woods, wading through the knee-high ferns all to the way to what I like to refer to as the Great Grandmother Apple Tree.

She is huge, with old broken limbs, and thick branches, and towers from out of the sea of ferns at the top of a hill with 3 other large apple trees below her. John Bunker stood there thoughtfully, a hand on her trunk, as if listening. “Apple trees like to grow at the edge. At the edge of a field, or the edge of a stream. They are trees that favor edges. This was the edge”. The edge of what used to be a field, and is now filled with trees, crowding out the sunlight.

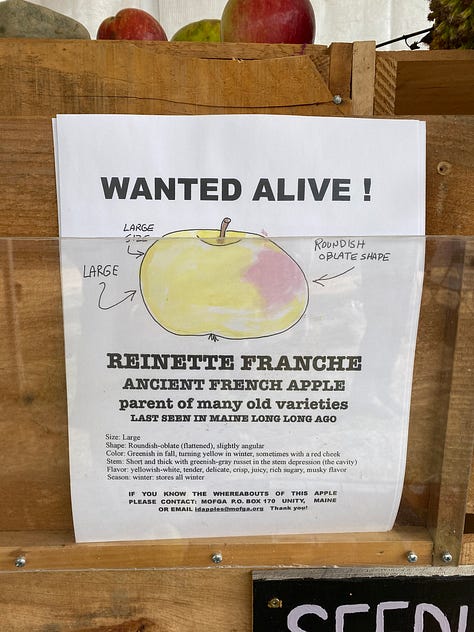

What a gift to be led through our apple orchard by this human. Later, we went to his talk. And there he was at the Common Ground Fair, with his display of heirloom apples from the orchard he tends with MOFGA, the Maine Organic Association, and “Wanted Alive” signs for old “parent” varieties he is looking for.

While on the walk through the forest, with John, we got to talking about the old stone walls running through it, and the accompanying Professor recommended a book called “Reading the Forested Landscape”, by Tom Wessels. Not long after that I saw that Tom Wessels was hosting an event at one of my favorite local organic farms: Northern Bay Organics, a regenerative organic no-till farm in Penobscot, just a short drive from us — that has adopted a “pay what you can” community model where the food is free and the farm accepts donations. Last weekend we were led through the farm’s forest in a small group by Tom Wessels. Under the towering elms, he explained the life of lichens and the duplicity of squirrels and acorns, that fog brings more nutrients to trees than rain, and the power of healthy soil to regenerate. My love language…

For now, we have decided that in lieu of going to the gym, we can pick up sticks in the forest, to clear off the walls lining the road. That should keep us busy til next Spring — apart from when the walls are covered with snow and I will sit happily by the wood burning stove planning our 2025 summer garden…

What a fabulous life you are leading. Such a beautiful description and how fortuitous to meet those great experts. It sounds like you have a fabulous documentary there.

Très intéressant:)