When I graduated from college and moved to Paris, it was the Reagan years, and I liked to say with a smirk that I was a political refugee. That said, despite my loathing of the Reagan administration, and though I could remember Woodstock happening when I was about 6, and tanks in the streets when DC was burning in 1968, while I lived abroad, I always thought of the US, or at least the idea of the US as a country that fundamentally stood behind the ideas of freedom and equality (even if it hadn’t quite figured out how).

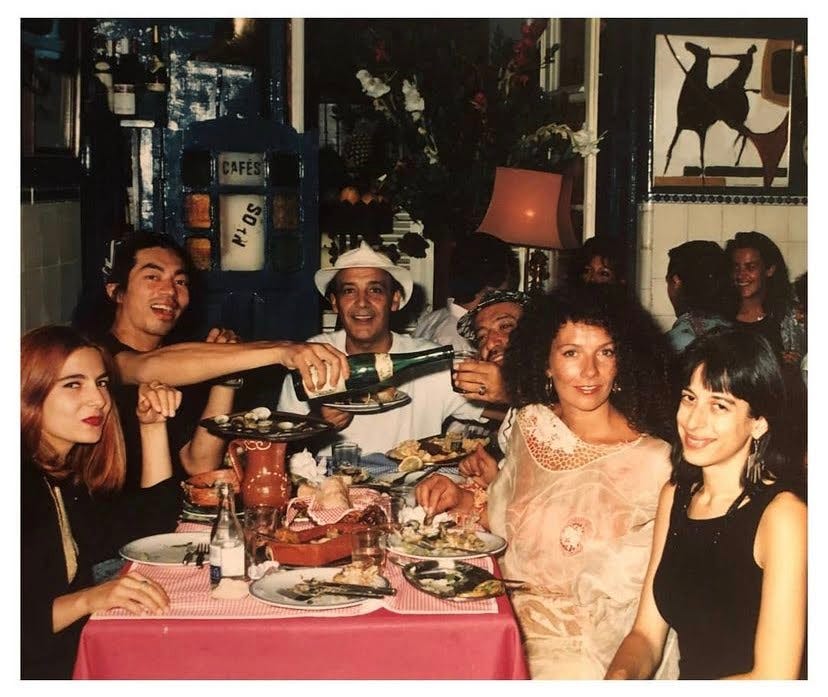

Around this time, through my work translating screenplays, I met Carlos Da Silva, a Portuguese producer living in Paris, in an encounter which developed into an 8 year relationship. Nearly 30 years my elder, he was a raconteur, a master at surreal humor and full of joie de vivre — and perhaps equally impressive to me: Carlos came from a time when men wore hats. I loved that he wore a hat. And tipped it, when appropriate, lowering his eyes politely.

Part of what also fascinated me about Carlos was his window into a life that was so far apart from my own lived experiences growing up in the US. From his stories of navigating the French film business in the 60’s and 70’s, when he acted in early Claude Lelouch short films, living and breathing the Nouvelle Vague as a film producer — steeped in the era’s challenges to authority and traditional movie-making — to his memories growing up in Portugal under Salazar, in the 40s and 50s, a world and time away from my American childhood.

Carlos had a particular fondness for provocative South American directors I had the opportunity to also get to know during our time together, and they were very politically engaged. While shooting a TV series in Rio de Janeiro, we were frequent guests of Nelson Pereira Dos Santos, the father of the Brazilian Cinema Novo — who used neorealism to show the harsh realities of Brazilian life under military rule that official media wouldn't acknowledge. I got to know Raul Ruiz, who had exiled from Pinochet’s Chile to Paris and was responsible for an iconic series of surrealist films with labyrinthine narratives that defied conventional storytelling, offering subtle resistance to both political oppression and Hollywood's narrative control. I remember him fondly, telling me with a wry smile about his work with a think tank on 'the two zeros'—'the one that stops at zero, and the one that goes on to the negative'—always the provocateur.

Then there was Ruy Guerra, who was not only García Márquez's chosen director for "Erendira," but also a committed political filmmaker whose Mozambican origins and leftist perspectives aligned with the revolutionary spirit of Latin American cinema. When I met him, he was completing "Me alquilo para soñar," a television miniseries shot in Cuba based on an original García Márquez screenplay—a collaboration that reflected both men's political sympathies and their shared artistic vision. Guerra's cinema, like his Cinema Novo contemporaries, used magical realist elements to encode political critique that might otherwise have been censored.

The creatives I got to know during my years abroad, were politically engaged directors and actors who, ironically, had figured in many of the movies my father had shown in his arthouse movie theaters when I was a kid growing up in DC (where Nixon sued him — and lost — after his motorcade drove past a crowd lining up to see the Swedish film “I am Curious Yellow”, one of the first “erotic” art films to come to the US). Ah, it all comes full circle.

Carlos told the story of a reverse meal he shared one late night, at a bistro on the Champs Elysées, with the future cast and director of the 1973 film, La Grande Bouffe. Hungry for a late night snack after a party, the group of friends had stumbled into this bistrot and started with a round of desserts, before working their way backwards through steak frites, to oysters, and eventually agreeing a film must be made about a group of friends who ate themselves to death. This is how La Grande Bouffe was born. Carlos somehow secured distribution rights for Spain, but Franco's regime banned it as a critique of the wealthy elites who supported fascist regimes. Busloads of curious Spaniards traveled to Andorra to watch the forbidden film, but Carlos never got to distribute it in Spain.

Not long into our relationship, we decided to move back from Paris to his native country, Portugal, which he had left some 30 years prior. We formed a Portuguese production and distribution company which launched with the distribution in Portugal of the iconic and chilling film the Vanishing, directed by George Sluizer. Outside of his opus of works, George had worked with Werner Herzog on his boundary-pushing films in Brazil, including 'Aguirre, the Wrath of God,' which used a 16th-century expedition as allegory for modern Latin American dictatorships. Herzog himself described the film as portraying 'the failure of imperialism 'in a way that remained 'really quite modern.' — a way that could still be found today in many Latin American countries."

Eventually, we co-produced a film with George as well, that Carlos and I co-wrote — a ghost story called Dying to Go Home about that space you inhabit as an immigrant where you don’t feel integrated in your new country, but equally your home country feels foreign to you once you’ve left. This was a dark comedy with an immigrant ghost trying to get his bones back to his homeland in order to find peace. (Spoiler: he finds peace once roots take in his new home — not by going back to his homeland.)

Living with Carlos in Lisbon for several years, the not-so-distant past that Portugal endured under the regime of Salazar, became more and more palpable, with Carlos’ childhood a further window into that life. Though he had lived in France for over 30 years, he was not immune from the impact of growing up in a bureaucratic Fascist regime. When we formed our Portuguese company one of the first things he had us do was to create a company stamp. A “carimbo”. It seemed more important to the validity of a document that it be stamped, than signed. I was perplexed. “What’s with the stamp”? “Isn’t a signature enough?” He was adamant. Every official letter or action needed to be stamped. Eventually I realized this was a holdover from growing up in fascism, where officials had to stamp documents. Rubber stamping is real. Without it, he didn’t think the document was real.

Carlos was also very superstitious — I’m sure this is connected to the heavy hand of church and state, that he grew up in. He wouldn’t walk under scaffolding: “if you do, you might come out in a different dimension”. No money could be left on the bed. (This could suggest some form of prostitution) Garlic had to have the green stems cut out and discarded “C’est indigeste.” (It’s hard to digest). Same with tomato skins and seeds “C’est pour les cochons” (that’s for the pigs)— his grandmother told him these things, and he told me.

He and his mother had moved into Carlos’ grandparents home after his parents divorced during a rare year when people in this Catholic country were given a 1-month hall pass to have divorces. Carlos carried the shame of this divorce in him like a vulnerable young child. He had seen the averted eyes of the people in the seaside town where he lived, looking away from his mother as she walked down the street, and sometimes I could still feel this sadness deep inside him. The shame of a divorce in a catholic country, in the 40s, was huge. He and his mother inhabited one floor of the family home where his grandparents also lived, and he spent hours in the kitchen with his grandmother watching and helping her cook. I’m assuming that some of the cooking skills, which he passed on to me, live on from his grandmother who showed him these things close to a century ago.

The Lisbon we inhabited in the late 80’s / early 90’s had only just been liberated from the hold of fascism — with the Carnation Revolution on the 25th of the April, 1974. It seemed like a distant past to me, but in retrospect it was quite fresh. The streets buzzed with nightlife as families happily sent their children out to enjoy themselves in a way they had never been able to do during the Salazar years. This was well before Portugal had become the tourist destination that it now is, and I loved living there, in this atmosphere of joy and freedom, with the pink light and balmy air perfumed by orange blossoms.

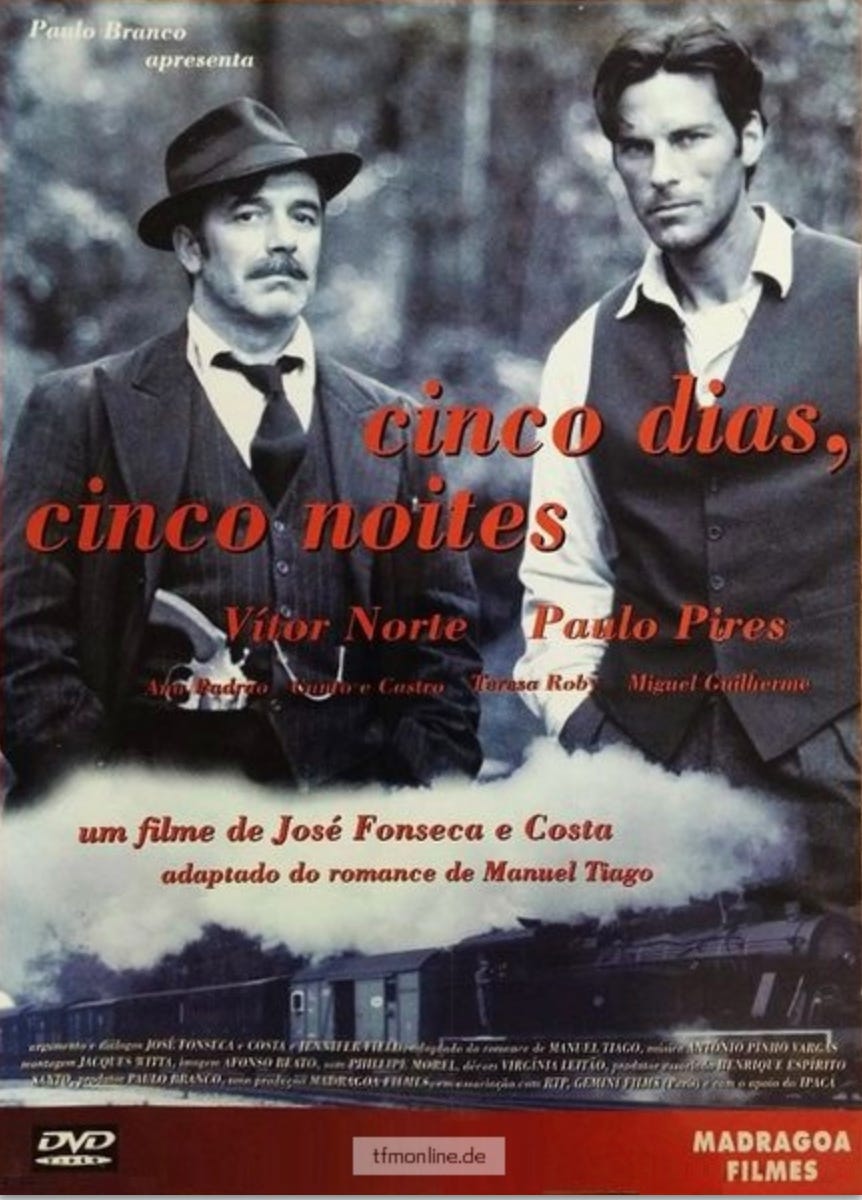

In Portugal, I also had the opportunity to work on another screenplay called Cinco Dias, Cinco Noites (Five Days, Five Nights), a film about the escape from fascist Portugal to Spain, over the mountains (with the help of a contrabandista) by a young activist who went on to lead the Communist party. It was an adaptation of an auto-biographical novel written under a pseudonym, by beloved Portuguese political leader Alvaro Cunhal — who left it behind during his dramatic escape from Forte de Peniche prison in January 1960. The manuscript was only returned to him after the 1974 Revolution. The story captured the fear and heavy atmosphere of life during the Salazar regime.

The window into this time was opened wider with Carlos’ childhood memories. Though he always said his grandfather was a good, honorable, kind man, I wasn’t blind to the fact that his grandfather was also the head of the Police in Setubal, Carlos’ home town. I couldn’t help wonder if Carlos had the full picture of what his grandfather might have done in this context, and the context of the secret police — the PIDE — still spoken of in hushed terms when I lived in Lisbon. My friends would point at a building in the neighborhood where we lived: “That was the PIDE headquarters. Terrible things happened there”.

Carlos had an incredible story he shared with me of an adventure he had as a very young teen growing up in sleepy Setubal (mostly known for it’s sardine canneries I believe) In those days, to keep shoes from wearing out, tacks were stuck into one’s shoe heels, and so Carlos and his friend would amuse themselves by grabbing onto the tailgates of lorries driving through the town, so that sparks would be thrown up from their shoes skidding across the cobblestones.

The game developed as Carlos and his friend figured out how to go from hanging from the tailgate, to jumping into the back of the truck. And then, one day, they devised a plan: they would each tell their mothers they’d been invited to spend a week at the other’s country house, but instead they would jump one of these trucks and see if they could get all the way to Spain. At this time, I’ll guess around 1948-1949, obviously, the borders were tightly shut, so this was an ambitious and risky game. They packed up some food and waited for an opportunity, and soon enough they were hidden in the back of a canvas-covered truck, headed away from Setubal. But the truck kept going for much longer than expected. Their packed lunches were nothing but crumbs by the time the bemused driver finally got to his destination several days later, and opened up the back of the truck, shocked and frightened to discover the stowaways. The boys had succeeded in traveling out of Portugal, but this wasn’t Spain. Around them was a devastated landscape of shelled buildings: it was post-war Hamburg!

The truck driver was horrified at being responsible for this unauthorized travel, and quickly shuttled the bewildered young boys to safety, to await him for a return trip in about a week. He had taken them to the safety of his Hamburg girlfriend, who lived in a bordello, where the two boys were mothered and coddled by the women there until the day they were smuggled back into the truck for the return trip. After a few days stop somewhere in the South of France, where they washed dishes in a restaurant and used their pay to visit the casino, the truck finally returned them to Setubal. Carlos tried to tell his mother of his adventure to Germany, but it was so incredibly far-fetched that she waved him away with his inventive stories. Until about a year later, when the truckdriver knocked on the door of the house to check in on them, and Carlos’ mother realized the truth of what had happened. Apparently she cried for a week. In the context of the tightly locked borders at that time, and post war Germany, the escapade goes down in Carlos history.

Thankfully this incident was without consequence (what could have possibly gone wrong?!), but Carlos told me other stories that didn’t end well. There was a family supper where one guest raised his glass to “Liberdade” (Liberty). Three weeks later, that family member disappeared, never to be seen again. A family member around that table must have turned him in.

And so now, when I see people being disappeared in America, these worlds that once seemed oceans apart are suddenly converging. Carlos' living memory lives on in mine, and I realize that to many Americans there is no connection or shared memory of life under a totalitarian regime, perhaps explaining how we are slipping so dangerously into authoritarianism, something I never imagined could happen to this degree in the USA, despite my criticism of past politics.

The living memory of the collaborators during Nazi times in Paris was still very much part of the consciousness when I lived there, and still lives on in me now. The living memory of bombs being dropped in London is still very much alive in the memory of my ex Mother-in-law, and now in mine. Closing libraries, and banning books might be an effort to erase our living memory and the fear of fascism, but I will also be looking out for the voices of dissent, in whatever forms they express themselves.

Carlos sadly passed away in 2008, just months after I moved to the US after 25 years living abroad, and not long after the last time I saw him. Before the move, with my then husband and 3 kids, we had visited the Algarve for a farewell stay with some dear friends, and Carlos took the train down from Lisbon to see us all. By then he walked with a cane, having lost some toes to diabetes, and I remember watching him when we dropped him off for his return train to Lisbon, slowly stepping through the train station with his cane, his ever-present hat on his head. Months later, when we were settled in California, he let me know he was going to have an operation on this throat. (He had been a heavy smoker for decades — as that entire generation was). I had wanted to call him after the operation, but decided to spare him using his voice. Two days later I got the devastating news there had been complications, and he had passed.

I imagine him in the other world, around a table, telling stories, provocative and playful, surrounded by beautiful angels, and above all, free. And hopefully he knows his living memories are still very much alive in me.

Love this! So interesting